Reflecting on how I build software lately, I noticed a pattern. I tend to write libraries in absolute isolation, as if they were open sourced and the world is watching along.

Let me try to explain why this works for me.

Where Theory Fails ¶

“The difference between theory and practice is that, in theory, there is none.”

We have all been schooled to isolate units of software into reusable components. Software engineering literature refers to this as separation of concerns since decades. It reduces the big problem into smaller non-overlapping problems.

We obviously try doing so, by putting related logic into modules, libraries and whatnot. Yet, in practice, so many real world projects fail at their attempts and end up evolving into something unnecessarily complicated.

The main problem with this is that it becomes increasingly hard to comprehend and reason about your software, not to mention the “increased fun” maintaining it.

Why is it so hard to actually achieve this in practice? Separating concerns apparently is easier said than done.

How Things Evolve ¶

The need for a new library often arises when solving a larger problem top-down. In the quest of solving a larger problem, you need to create a smaller component first that is required to get to a fully working solution. This is what most of our work as engineers is about—while solving a larger problem, we run into bumps along the road. When we do, we stop, fix the bump, and continue on our journey to solving the large problem.

In our rush to arrive at our end destination, we want to fix any bumps as quickly as possible. For many good reasons, mostly. We might have a deadline, or we are afraid to get lost in details and lose focus on the bigger problem we were actually solving.

In short, we tend to see those bumps as unsolicited chores that are blocking us and we want to spend as little time as possible at overcoming them. From a quality perspective, however, this may not be the best route to take. So the least you can do is create that Technical Debt ticket, feel less guilty, and move on :)

I’ve never seen a project work any more glorious than this.

Step Back, Breathe, Accept, Open Source ¶

Running into these bumps sucks. You’re frustrated that you’re held up and are continuously thinking: dammit, I don’t want to deal with this now. The reality often is that you don’t have a choice.

Instead, step back a few steps, take a deep breath, and accept that you’ll have to spend more time on this problem than budgeted. This enables the mental rest to make a good engineering decision without too much frustration emotion involved.

What I like to do at this moment, is to start a new open source project.

Not necessarily a public one, but I do set it up like it is and actually

consider it to be, or eventually become, open. I start out with a README

decribing the problem and the API I’d like it to have. And in the case of

Python, I also create a setup.py so integrating this into the original

project is only a pip install away.

Then, just start implementing it.

Let me try to highlight the benefits this approach provides.

You’re More Likely To Do It Right ¶

The pressure you get from pretending (or knowing) that many others will read your code, pushes you to do it right. I’d ask myself continuously: would this be an API that I’d show off to the outside world and be proud of? Could I truly explain this API in a README so that people would understand? If not, I don’t implement it like that and push harder.

Many eyeballs make you feel more responsible. Writing stuff in private for yourself, doesn’t.

No Cheating ¶

A big difference between starting an actual new project, or developing it as one-of-many internal libraries, is that it’s impossible to rely on other parts of the end product. For example, that convenient project-specific helper function you already wrote is easily included in a module, but not so much in another project.

In an open source project, you simply cannot cheat on yourself this way and you’re forced to come up with a better solution. This might feel inconvenient at first, but remember that it’s easy to write complex software and it takes more care and dedication to write simpler software.

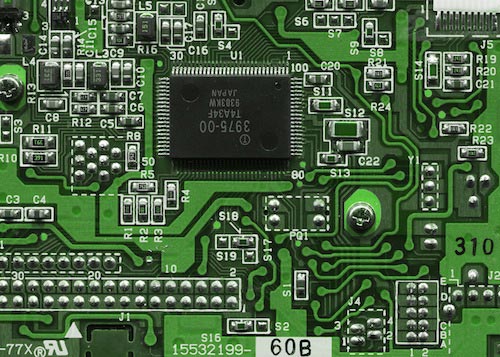

As a way of visualising this approach: compare programming to electrical engineering for a minute. Say you have to create a circuit board of some sort.

The chip on this board is analogous to an open source software project. Its internals are nicely abstracted away, the pins of the chip form its API, it’s probably well-tested, well-documented and can be reused immediately. It is physically impossible to connect to any of the internals of it—which is exactly the point of abstraction.

Looking at the circuit board, everything about this falls into place pretty obviously.

As programmers, we often fool ourselves that we’re isolating logic into modules/libraries, while in fact we’re merely organising it. Modules will oftentimes still contain project-specific dependencies. (As a good litmus test, move that module to an empty directory and use it. If it breaks, it wasn’t truly isolated.)

The curse with programming is that it’s so easy to create these dependencies.

They are only one import statement away. Developers live in a world where

that temptation continuously lurks.

But by isolating code into a stand-alone project, you can remove this temptation wholly, thereby reducing ways of cheating on yourself.

Simplicity Pays ¶

Another big benefit of truly isolating your libraries this way, is that you are forced to think about its API. It’s the only way of interacting with the library after all. Doing this, you’ll naturally feel the urge to simplify. Complex APIs lead to complicated documentation and complex tests. The opposite applies, too, fortunately, and you’ll naturally be inclined to simplify.

A concrete example of this: When you are hacking in a web environment, you most

likely have “the request” or “the DB connection” at your disposal any time.

When you put your library in a module, it’s easy for these to become implicit

dependencies of your library. Your library may pretty well work outside of

a request context, however, and in fact, the only thing you actually need from

the request could be a User instance. When you build your library as

a separate project, these decisions fall into place effortlessly. In the end,

this makes your library more decoupled, more generic, and overall cleaner. And

as such, simpler.

True Isolation™ is the ultimate catalyst of simplicity.

Sharing Can Pay Off, Too ¶

Even if you’re only using this technique privately to produce better software for yourself, this pays off already in a technical sense.

But open sourcing can also pay off in non-technical ways. When it fits your company’s strategy, you now have the choice to actually publish your project at any time, since it’s been written for the public from the beginning. If it solves a common problem, others may like it and take interest in following it or even contributing to it. This may open up a whole new world of users providing feedback and improvements through code or documentation contributions.

Your company may come across as an interesting place to work for to talented people. Your open source project can be your company’s banner. We’ve seen this with companies like Joyent (of Node.js fame), 10gen (of MongoDB fame) and Opscode (of Chef fame), just to name a few. Open sourcing has been an important marketing value to these companies and they have attracted many talented folks through their high-quality work.

Just always remember that simpler projects have a much lower barrier for contributors, so these are more likely to receive patches. Which by itself is another good reason to simplify your libraries :)

How I Built RQ ¶

Many of the things I created recently, I created this way. Back a few months ago, I needed a super-simple solution to put work in the background. I was working on a startup idea, which I was creating a proof of concept for. It was a small Flask web app, and I used this snippet initially to offload work to the background. It did the work fine, but I soon needed it to do more, so I kept tweaking it until it was no longer a snippet, but a library. Although it was nicely organised in a directory, it was still tailored to the specific product I was creating.

This is where I decided to step back and started building that library like an open source project, which became RQ, of course. After using it privately for about four months, its API kept changing quite a bit, but its use became more general over time. I started reusing it for other projects I was working on, until I considered it stable enough. I believed it could be of help to other Python engineers, so I decided to open source RQ in March.

Eventually I dropped the original startup idea, but I still have RQ. Had I not open sourced it, it would now be buried with the rest of that project’s code.

Open sourcing pays off. Even if you do it in private.